Elements of Successful Fiction

If you are partaking in NaNoWriMo, then you have made past the halfway mark by now. Congratulations!

We hope that this article will provide prompting to spur you on to the finish line!

The best fiction touches the deep layers in us. A writer achieves this effect by embedding dozens of techniques into his or her story. – Jessica P. Morrell

Dramatic Question

- Compelling fiction is based on a single, powerful question that must be answered by the story climax.

- This question will be dramatized chiefly via action in a series of events or scenes.

- Examples:

- If you are writing a romance, the question always involves whether the couple will resolve their differences and declare their love.

- In a mystery the dramatic question might be will Detective Smith find the serial killer in time to prevent another senseless death?

- In The Old Man and Sea, the dramatic question is will Santiago catch the big fish and thus restore his pride and reputation?

- Assignments:

- What is the dramatic question in Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone?

- What is the dramatic question in Stephanie Myers’ Twilight Saga?

- Here is a cool article from The Atlantic magazine that will challenge everything that you’ve ever thought about the Twilight Saga series: https://www.theatlantic.com/entertainment/archive/2012/11/at-its-core-the-twilight-saga-is-a-story-about/265328/

- Examples:

An Intimate, Simmering World

- An intimate world isn’t created by merely piling on details.

- It means your story world has the resonance of childhood memories, the vividness of a dream, and the power of a movie.

- An intimate, simmering world is filled in with shadows and corners and dogs and ice cubes and the sounds and smells of a dryer humming on wash day and a car blaring past, with pop music shaking the windows. These details lend it authority, potency, and a palpable physical existence.

- Diana Gabaldon’s The Outlander Series simmering details make this time-travel, fantasy, horror, science fiction extremely believable and immersive fiction.

An intimate story takes us to a specific place and coaxes us to remain there. An intimate story is lifelike and feels as real and complicated as the world the reader inhabits. When he finishes the final pages, and leaves the story world, he should feel the satisfaction of the ending, but also a huge sense of loss. Like a friend has moved to another town just when the friendship had reached a level of closeness and trust. – Jessica P. Morrell

Characters Built from Dominant Traits

- Create main characters with dominant and unforgettable traits as a foundation of personality.

- These traits will be showcased in the story events, will help him achieve or fail at goals, and will make the story person consistent.

- For example, Sherlock Holmes’ dominant traits are that he is analytical, Bohemian, opinionated and intelligent. These traits are showcased in every story he appears in along with secondary and contrasting traits. When the character first appears in the first scene, he arrives in the story with his dominant traits intact.

- Outlander’s Claire and Jamie.

- Lord of the Rings‘ Gandolf

- Lisa Wingate’s Before We Were Yours’ villain Georgia Tann

Emotional Need

- The protagonists and main characters are people with baggage and emotional needs stemming from their pasts. These needs, coupled with motivation cause characters to act as they do.

- For example, in Silence of the Lambs Clarisse Starling is propelled by childhood traumas to both succeed and heal the wounds caused by the death of her father.

- Robert Dugoni’s Tracy Crosswhite in his The Tracy Crosswhite series.

Significance

- The storyline focuses on the most significant events in the protagonist’s life.

- Example: Robert Dugoni’s Tracy Crosswhite searches for the killer of her sister in his The Tracy Crosswhite series.

- Craig Johnson’s Longmire series – Sheriff Walt Longmire whose wife was murdered.

Motivation Entwined with Backstory

- Motivation, the why? of fiction, is at the heart of every scene, fueling your character’s desires and driving him to accomplish goals.

- Motivation provides a solid foundation for the often complicated reasons for your character’s behaviors choices, actions, and blunders.

- Motivating factors provide trajectories for character development, as a character’s past inevitably intersects with his present.

- Your character’s motivations must be in sync with his core personality traits and realistically linked to goals so that readers can take on these goals as their own.

Desire

- Desire is the lifeblood of fictional characters.

- Not only do your characters want something, but they also must want something badly.

- You can bestow on your character flaming red hair, an endearing, crooked grin and a penchant for chocolate and noir movies, but if she doesn’t want something badly, she’s merely a prop in your story, not a driving force. But if she wants to win the Miss Florida contest, take over her boss’ job, or become the first female shortstop for the Atlanta Braves, then you’ve got a character who will make things happen and a story that will be propelled by desire.

- The Ring from Lord of the Rings is a perfect example of a symbol of desire on so many different levels.

Threat

- Fiction is based on a series of threatening changes inflicted on the protagonist.

- In many stories, these threats force him or her to change or act in ways he or she needs to change or act.

- Often too, what the protagonist fears most is what is showcased in a novel or short story. It can be fear of losing his family, job, or health with a dreaded outcome.

- Fear of losing to a threat or threats provide interest, action, and conflict.

Causality

Events in fiction are never random or unconnected. They are always linked by causality with one event causing more events later in the story, which in turn causes complications, which cause more events, which cause bad decisions, etc.

Please visit our blog post on The Inciting Incident.

Inner Conflict

- A fictional character doesn’t arrive at easy decisions or choices.

- Instead, he is burdened by difficult or impossible choices, particularly moral choices, that often make him doubt himself and question his actions.

- Inner conflict works in tandem with outer conflict—a physical obstacle, villain or antagonist–to make the story more involving, dramatic, and events more meaningful.

Complications

- A story builds and deepens by adding complications, twists, reversals, and surprises that add tension and forward motion.

- Plots don’t follow a straight path. Instead, there are zigzags, dead ends, and sidetracks.

- Complications create obstacles and conflict, cause decisions to be made, paths to be chosen.

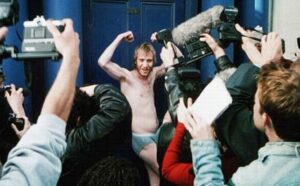

- My favorite complication is one from Notting Hill when Spike is standing outside in his underwear strutting around with the paparazzi going wild for a peek at Anna Scott. How could Anna and William ever expect that complication?

Midpoint Reversal

- The middle of a novel comprises more than half its length.

- At about the midpoint of most novels, a dramatic reversal occurs. The hunter becomes the hunted; a second murder occurs proving the detective has been wrong in his suspicions; a former lover arrives in town to complicate a budding romance.

- This reversal keeps the middle from bogging down and becoming predictable and also breathes new life and often a new direction into the story.

Satisfying Ending

- Every story needs an ending that satisfies the reader while concluding the plot.

- A satisfying ending does not have to be “happy” or victorious or riding off into the sunset.

- The final scenes, when the tensions are red hot and the character has reached a point of no return, must deliver drama, emotion, yet a logical conclusion.

- This is not to suggest that every plot ends with a shoot-out or physical confrontation.

- Some endings are quieter, more thoughtful. Some endings are ambivalent, some a dramatic or a violent clash of wills.

- However, there is always a sense that all the forces that have been operating in your story world have finally come to a head and the protagonist’s world is forever changed.

We are cheering you on to the Finish Line! You can do it!

Keep writing, keep dreaming, have heart. Jessica

Jessica Morrell is a top-tier developmental editor and a contributor to Chanticleer Reviews Media and to the Writer’s Digest magazine. She teaches Master Writing Craft Classes at the Chanticleer Authors Conference that is held annually along with teaching at Chanticleer writing workshops that are held throughout the year.

Keep creating magic! Kiffer

Kathryn (Kiffer) Brown is CEO and co-founder of Chanticleer Reviews and Chanticleer Int’l Book Awards (The CIBAs) that Discover Today’s Best Books. She founded Chanticleer Reviews in 2010 to help authors to unlock the secrets of successful publishing and to enhance book discoverability. She is also a scout for select literary agencies, publishing houses, and entertainment producers.

Chanticleer Editorial Services – when you are ready

Did you know that Chanticleer offers editorial services? We do and have been doing so since 2011.

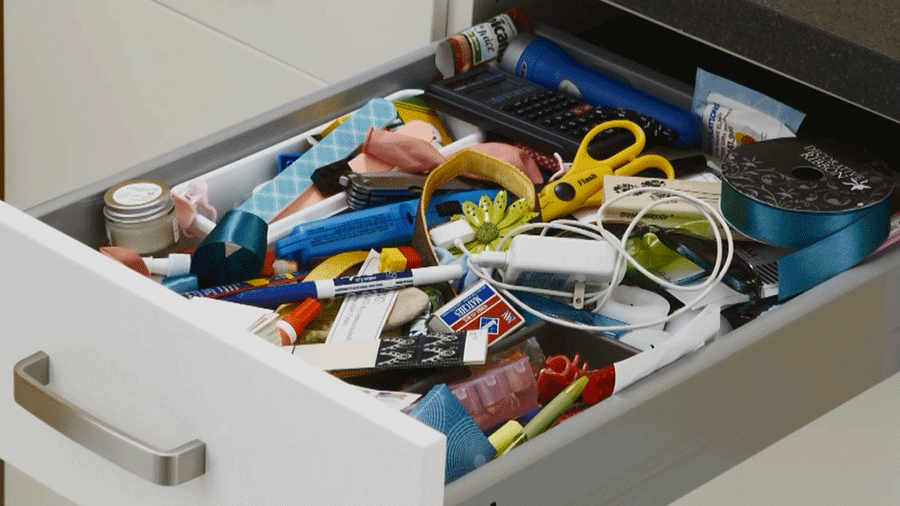

Tools of the Editing Trade

Our professional editors are top-notch and are experts in the Chicago Manual of Style. They have and are working for the top publishing houses (TOR, McMillian, Thomas Mercer, Penguin Random House, Simon Schuster, etc.).

If you would like more information, we invite you to email Kiffer or Sharon at KBrown@ChantiReviews.com or SAnderson@ChantiReviews.com for more information, testimonials, and fees.

We work with a small number of exclusive clients who want to collaborate with our team of top-editors on an on-going basis.Contact us today!

Chanticleer Editorial Services also offers writing craft sessions and masterclasses. Sign up to find out where, when, and how sessions being held.

A great way to get started is with our manuscript evaluation service. Here are some handy links about this tried and true service: https://www.chantireviews.com/manuscript-reviews/

Writer’s Toolbox

Thank you for reading this Chanticleer Writer’s Toolbox article.

Add this checklist to your Writer’s Toolbox.

Add this checklist to your Writer’s Toolbox.

Chanticleer Editorial Services Writer’s Toolbox Series

Chanticleer Editorial Services Writer’s Toolbox Series