“I try to pull the language into such a sharpness that it jumps off the page. It must look easy, but it takes me forever to get it to look so easy. Of course, there are those critics — New York critics as a rule — who say, Well, Maya Angelou has a new book out and of course it’s good but then she’s a natural writer. Those are the ones I want to grab by the throat and wrestle to the floor because it takes me forever to get it to sing. I work at the language.” ~ Maya Angelou

~ Maya Angelou Source: Source: The Paris Review Interviews: Volume IV

Maya Angelou’s website: https://www.mayaangelou.com/

Writing Advice from Jessica Page Morrell – Lassoing the Jottings and Crafting Words

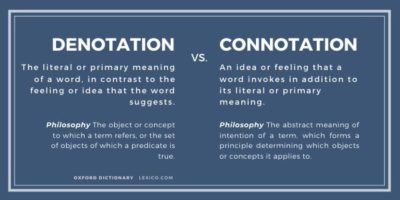

I’ve been purging my office and as I toss old receipts and rearrange books I’m finding scraps of paper with scrawls and tidbits on them. So I’m lassoing all these jottings. A single word on the back of an envelope says ‘waft’. Now, waft is in my vocabulary, and I’ve used it in writing, but these lists always inspire me. Another envelope back includes: pinprick, squatter, fusty, quisling, shacky, gawk, wheedle, moonwalk, shirk, bupkis, wraith, servile, scuttle, torpor, badger. Because if you’re not constantly gathering words you’re not growing as a writer.

“…if you’re not constantly gathering words you’re not growing as a writer. – Jessica Morrell

My next step is to figure out where to record these snippets. If you’re an analogue type like I am, you might have notebooks stashed all over the place. In fact, I’ve decided to stash one in my car’s glove box. Wondering why I haven’t done this years ago since I often hear information on NPR that I scribble on my hand as I’m driving. I’ve written here before about keeping a writer’s notebook, a lens to the world. Some jottings will land in my current writer’s notebook, while others will end up in specific ongoing projects.

Ruminate Productively. Question Thought Cycles

Another note says: Ruminate productively. Question thought cycles. This one struck me hard. There was a tragic death in our family 3 weeks days ago and during the final weeks of my niece’s life, my thoughts returned again and again to her suffering. And her parents’ suffering. And, of course, I suffered too, sad, worried for them all, grieving the unfairness of her shortened life. I also tracked memories along years of family events and unearthed painful memories and tracked over old scars. In other words, unproductive ruminations.

Sometimes it felt like I needed a lifeline to yank me free of this painful undertow. So I’ve turned to poetry before falling sleep and reading verses during the day. Such solace. And I’m falling into the poems and marveling at the poet’s imagery and turns of thought. Poetry can teach all writers. Poetry can help heal bruised and shattered hearts.[Editor’s Note: See Links above for Maya Angelou]

Poetry can teach all writers. Poetry can help heal bruised and shattered hearts. – Jessica Morrell

Track Complicated Emotions and Contradictory Thoughts

Here’s another morsel: Track complicated emotions and contradictory thoughts. Since I’ve been quarantining for about a century now I’m getting worn down from too much time spent inside my head. Some days thoughts go skittering into strange places which then scare up unexpected emotions. Not always welcome emotions. So, as I ‘hear’ unhelpful inner talk, I try to stop myself. Then I backtrack into whatever I was thinking or feeling. Slow it all down and linger there. Figure out where the thought originated. Listening in to a hidden (or noisy) part of myself. Then, as I’ve been telling myself for years, thoughts aren’t like the weather. I can do something about them; question or entertain them, discard, or act on them. Instead of allowing a storm to brew.

If you’re not prone to rumination be on the lookout for these complicated emotions on a screen or while reading a novel. For example, don’t you love it when you witness a cocktail of emotions flicker across an actor’s face? Maybe as a painful realization dawns or a joyful understanding blooms. How would you write that? Sir Anthony Hopkins starring in The Remains of the Day as the fusty head butler is an excellent example of how tiny face muscles can express a wide range of emotions.

Contradictions

But let’s get back to contradictions. I taught online workshops last fall and in one workshop on subplots I explained the potency of contradictions while writing fiction. Contradictory needs and wants (or desires) within your main characters create delicious conflict. In The Remains of the Day, Hopkin’s character Stevens is at war with the truth. He’s blinded by his loyalty to his employer, a Nazi sympathizer, and clings to his duties instead of risking emotional intimacy–needs he dare not admit to. His elderly father dies alone while Stevens tends to an important dinner party and ignores the housekeeper’s–played impeccably by Emma Thompson– interest in him. The film is based on The Remains of the Day by Kazuo Ishiguro and is written as a first-person account by Stevens, a sometimes unreliable narrator.

You often see this dynamic at work in romance plots and subplots. For example, a woman is attracted to bad boy types, but deep down she longs for marriage, stability, and kids. This scenario played out in Bridget Jones Diary by Helen Felding where readers and viewers recognized what was best for Bridget, but she did not. Bridget was beginning a new year and diary by vowing to cut down on cigarettes, alcohol and calories. Also on her list was to find a stable man, but of course, chaos ensued in the form of a fling with a bad boy. He was played with aplomb by Hugh Grant in the hit film version, while she overlooked stable lawyer Patrick Darcy (Colin Firth) until it was almost too late.

Or a former addict or alcoholic has become clean and sober. All is well, until he is somehow triggered and then slips back into the bottle or ends up visiting his dealer. Meanwhile, as your reader is begging “do not go into that liquor store. Do not screw this up.” And this means your reader might be feeling contradictory feelings too–sympathy for the addiction, but enraged at the character for buckling under pressure.

Contradictions create suspense and tension. Stay tuned because I’m going to cover this in more depth in the future.

And as an aside: Villains MUST Deliver

This note was scrawled on a legal pad as I was reading a recent client’s manuscript: Villains MUST deliver. If you plop a villain or villainous group into your story they need to embody some form of evil and profound threat. He/she/they cannot remain offstage throughout. If your villains don’t threaten or scare your protagonist up close and personal, then fix the bad guy or your plot.

Immersive Reading Experience = Resonating with Readers

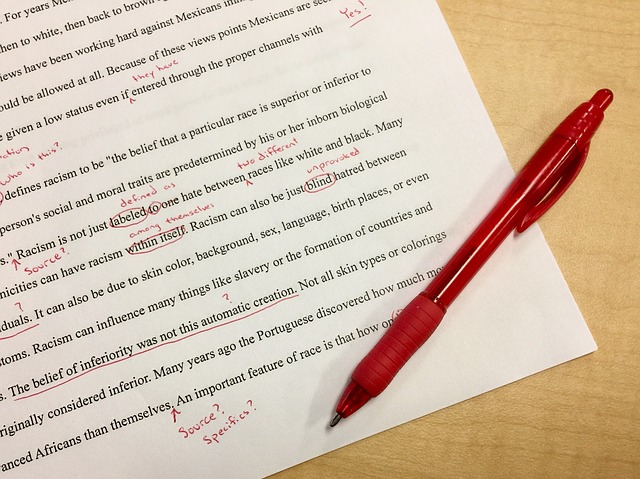

These days my notebooks are filled with mannerisms and reactions from the novels I read. In my editing work I notice that writers use the same emotional responses in their stories. Characters repeatedly look down, shrug, or are wide eyed. I read a novel recently where the author used ‘deadpanned’ five or six times. By the third deadpan, I was wincing.

Another reason to study other writer’s techniques is to create a more immersive reading experience. If you nail aftermaths or the viewpoint character’s experiences they will resonate with readers. Such as: startled chuff of laughter, a brittle silence settled between them, staring at him with dead, dark eyes, she flinches, settling uncomfortably, his heart started clattering around in his chest.

Write Your First Draft with Everything You Got

Don’t worry about finding the perfect words, the right words on your first draft. Just get your story out of your brain and into words.

Then put the whole thing away for a few weeks or months. Come back to your draft with fresh eyes to see if the story concept is worth your editing time. Meanwhile, start a new story while this one simmers on the proverbial back burner. Have you fallen in love for one or the other?

Here are two links that may prove helpful in unspooling the story in your brain onto the page:

How to Write Your Story in Four Weeks

Keep writing, keep dreaming, have heart. Jessica

Jessica Morrell is a top-tier developmental editor and a contributor to Chanticleer Reviews Media and to the Writer’s Digest magazine. She teaches Master Writing Craft Classes at the Chanticleer Authors Conference that is held annually along with teaching at Chanticleer writing workshops that are held throughout the year.

Chanticleer Editorial Services – when you are ready

Did you know that Chanticleer offers editorial services? We do and have been doing so since 2011.

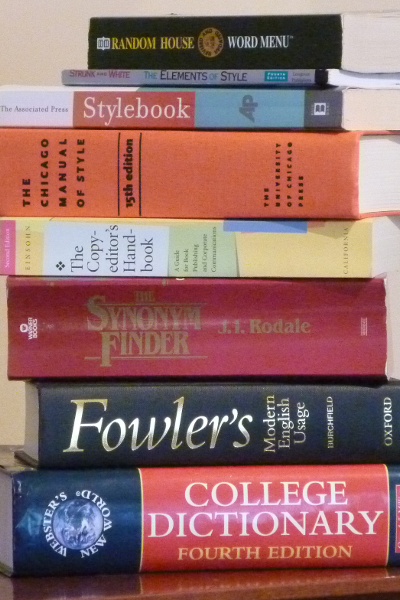

Tools of the Editing Trade

Our professional editors are top-notch and are experts in the Chicago Manual of Style. They have and are working for the top publishing houses (TOR, McMillian, Thomas Mercer, Penguin Random House, Simon Schuster, etc.).

If you would like more information, we invite you to email Kiffer or Sharon at KBrown@ChantiReviews.com or SAnderson@ChantiReviews.com for more information, testimonials, and fees.

We work with a small number of exclusive clients who want to collaborate with our team of top-editors on an on-going basis. Contact us today!

Chanticleer Editorial Services also offers writing craft sessions and masterclasses. Sign up to find out where, when, and how sessions being held.

A great way to get started is with our manuscript evaluation service. Here are some handy links about this tried and true service: https://www.chantireviews.com/manuscript-reviews/

And we do editorial consultations. for $75. https://www.chantireviews.com/services/Editorial-Services-p85337185

Writer’s Toolbox

Thank you for reading this Chanticleer Writer’s Toolbox article.

Writers Toolbox a few more Helpful Links:

Learn from the BEST!

Learn from the BEST!

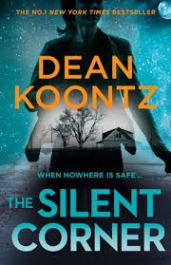

I’m not suggesting you skip plotting or structure, I’m suggesting you plan for an overall tone and mood from the get-go. I’ve rarely given this advice for a first draft before, but then I started reading Dean Koontz’ Jane Hawk series. And I’ve been giving a lot of thought to why the novels are bestsellers, what works and what doesn’t quite work.

I’m not suggesting you skip plotting or structure, I’m suggesting you plan for an overall tone and mood from the get-go. I’ve rarely given this advice for a first draft before, but then I started reading Dean Koontz’ Jane Hawk series. And I’ve been giving a lot of thought to why the novels are bestsellers, what works and what doesn’t quite work.

including the safety of her beloved 5-year-old Travis.

including the safety of her beloved 5-year-old Travis.

Craig Anderson before a cup of coffee…

Craig Anderson before a cup of coffee…