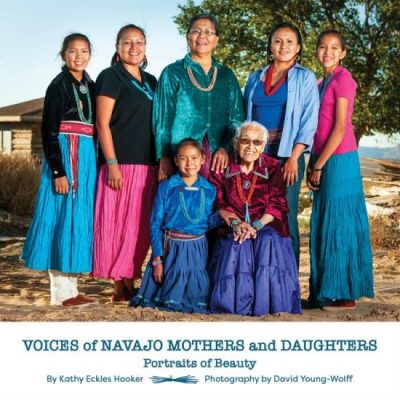

Voices of Navajo Mothers and Daughters: Portraits of Beauty by Kathy Eckles Hooker is a heartwarming work exploring the relationships between Navajo mothers and daughters, their connections with each other and their families, and their hopes and dreams for their children as they encounter a world far removed from their traditional lives.

In these insightful interviews with Navajo women—grandmothers, mothers, and daughters—the twenty-one families that the author spoke to talked about their backgrounds and histories. They contrasted how the elder women grew up compared to their daughters and granddaughters (such as the lack of amenities like electricity, running water, or internal combustion vehicles). And they explored the many ways that traditional matriarchal Navajo culture continues to enrich their lives today.

David Young-Wolff’s memorable, warm photographs of the interview subjects let us see the faces behind the stories. The charming presentations of the women, often with the backdrop of the land they grew up in and even of the family hogan, the traditional Navajo home, give the reader insight into the closeness between the generations and the natural and human environments that have shaped their lives.

The thoughtful tales these women tell are interspersed with painful reminiscences about points in American history that changed their culture’s ways of life. Events such as the Long Walk, in which more than 10,000 Navajo were forcibly marched by the US military to a reservation in what is now New Mexico, and the Navajo-Hopi Land Dispute, the judicial results from which echo even now.

In an outer society so dependent on cars, the elder women note how they were dependent on horse and buggy in their younger years. One woman recalls a memory of wonder when she saw a car for the first time. For some, water was only available by walking a certain distance to a well, and during times of drought, only used for feeding livestock or drinking.

In addition, they tell stories about life in traditional homes. Sometimes these women remember their homes warmly and sometimes not. One family speaks of the heartbreak of having a home destroyed and the pets and livestock killed by persons unknown, despite being on good terms with their neighbors.

The interviews in each case mention how the elders emphasized the need for education. But sometimes that “education” came in the form of abusive boarding schools that tried to erase native culture from the children they taught.

Language is an especially important issue discussed by the women, both young and old.

Only one of the families interviewed had a daughter who went to a boarding school that taught both Navajo and English. In the majority of cases, speaking Navajo was actively discouraged at the boarding schools. The disconnect of having to learn English to participate in the dominant American culture reflects on their lives and families even now.

Then there are stories about traditional ceremonies, specifically about the kinaaldá, a four-day ceremony celebrating the girl’s first menses. The women tell warm and humorous tales about what’s involved (including running every day for four days, each day longer, to make sure the young woman is strong enough to withstand what her life will entail), and they describe the trials and tribulations of baking a cake that family and friends will enjoy… but the girl herself cannot.

This book reveals how traditional culture has informed and continues to infuse the daily lives of Navajo women. Stories about arranged marriages, some expected and some a surprise (in one case only finding out the young woman is getting married the next day!), are eye-openers and provide food for thought.

One of the recurrent themes that shape these women’s stories is the question of how to support their children and how the next generations would be educated and grow to support themselves. The traditional art of weaving was a major or even sole source of income for a significant number of women in the book. Some of the elder women recount how they discouraged learning the art so that their daughters could do better than they did. In turn, some of the daughters mourned that they never learned the traditional art, feeling bereft of a connection to their ancestors.

Questions about what wisdom and skills we choose to pass along to our children are of course not unique to Navajo women; however, readers will enjoy Hooker’s way of illuminating this particular window into Navajo culture from the women who so graciously shared their journeys.

Voices of Navajo Mothers and Daughters: Portraits of Beauty by Kathy Eckles Hooker, is a deeply moving, must-read for mothers and daughters everywhere, and one book we highly recommended!