Many writers struggle to create vibrant and complex secondary characters. After all, complicated main characters are hard enough to create. Memorable secondary characters, however, can make or break a story. Think about Yoda (Star Wars), Pippin (LOTR), Jane Bennet (Pride and Prejudice), Thomas Pullings (the Aubrey – Maturin series by Patrick O’Brian), and …

I always view secondary characters as a measuring stick for a writer’s prowess. Jessica

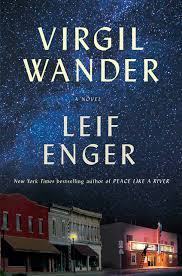

Here’s a vivid example of a memorable secondary character from Leif Enger’s beautiful Virgil Wander.

His name is Rune–so here’s a simple trick, give your characters resonant names.

In this case, rune has mystical, mysterious associations. The day after the protagonist Virgil survives a car accident in the opening moments of the story he walks to the waterfront of the forbidding, ever-changing Lake Superior. Enger is introducing an oft-used device: a mysterious Stranger comes to town.

I ended up at the waterfront. It’s not as though there’s any other destination in Greenstone. The truth is that I moved here largely because of the inland sea. I’d always felt peaceful around it–a naive response give it fearsome temper, but who could resist that wide throw of horizon, the columns of morning steam? And the sound of a continual tectonic bass line. In a northeast gale this pounding adds a layer of friction to every conversation in town.

At the foot of the city pier stood a threadbare stranger. He had eight-day whiskers and fisherman hands, a pipe in his mouth like a mariner in a fable, and a question in his eyes. A rolled-up paper kite was tucked under his arm–I could see bold swatches of paint on it.

There was always a kite in the picture with Rune, as it turned out.

He watched me. He carried an atmosphere of dispersing confusion, as though he were coming awake. “Do you live in this place?” he inquired.

I nodded.

“Is there are motor hotel? There used to be a motor hotel. I don’t remember where.”

His voice was high, with a rhythmic inflection like short smooth waves. For some reason it gave me a lift. He had a hundred merry crinkles at his eyes and long-haul sadness in his shoulders.

“Not anymore–not exactly.” If I’d had more words, I’d have described Greenstone’s last operational motel, the Voyageur, a peeling L-shaped heap with scraggy whirlwinds of litter roaming the parking lot. Though technically “open,” the Voyageur is always full, its rooms permanently occupied by the ower’s grown children who failed to rise on the outside.

“Oh well,” he said,shaking himself like a terrier. He peered round at the Slake International taconite plant, a looming vast trapezoid which had signified bustling growth in the 1950s and lingering decline ever since. Its few tiny windows were whitewashed or broken; its majestic ore dock rose out of the water on eighty-foot pilings and cast a black-boned reflection across the harbor. No ship had loaded her in so long that saplings and ferns grew wild on the planking. We had a little forest up there. I looked at the kite scrolled under his arm. He’d picked the wrong day for that, be then he looked like a man who could wait.

He said, “You here a long time?”

“Twenty-five years.”

At this something changed in him. He acquired an edge. Before I’d have

said he looked like many a good-natured pensioner making do without a pension. Now in front of my eyes he seemed to intensify.

“Twenty-five years? Perhaps you knew my son. He lived here. Right in this town,” he added looking round himself, as though giving structure to a still-new idea.

“Is that right. What’s his name?”

The old man ignored the question. He pulled a kitchen match from his pocket, thumbnailed it, and relit his pipe, which let me tell you held the most fragrant tobacco–brisk autumn cedar and coffee and orange peel. A few sharp puffs brought it crackling and he held it up to watch smoke drift off the bowl. The smoke ghosted straight up and hung there undecided.

Did you notice how this small scene multi-tasks?

Techniques to borrow:

- Sharply observed first impressions (carried an atmosphere of dispersing confusion as though coming awake, a good-natured pensioner making do without a pension, looked like a man who could wait)

- Props (kite and tobacco, kitchen match, pipe)

- Smells (tobacco)

- Iconic or mythic comparisons (rune, mariner in a fable)

- Indelible physical features: (fisherman’s hands, question in his eyes, a hundred merry crinkles as this eyes and a long-haul sadness to his shoulders)

Here’s a tip: When you need to describe a character or objects or setting ask yourself what does this remind me of?

As you walk around your world, really notice your surroundings and ask yourself the same question.

The next post will be about noticing and nurturing your imaginings with paying attention to small details with a novelist’s eye.

Here is the link to Part One of the Essence of Characters series: https://www.chantireviews.com/2019/06/01/essence-of-characters-part-one-from-the-jessica-morrells-editors-desk-writers-toolbox-series/

Until then, Keep writing, keep dreaming, have heart. Jessica

Jessica Morrell is a top-tier developmental editor and a contributor to Chanticleer Reviews Media and to the Writer’s Digest magazine. She teaches Master Writing Craft Classes at the Chanticleer Authors Conference that is held annually along with teaching at Chanticleer writing workshops that are held throughout the year.

A Chanticleer Reviews – Writer’s Toolbox blog post on Character Development by Jessica Page Morrell

Did you know that Chanticleer offers editorial services? We do and have been doing so since 2011.

And our professional editors are top-notch and are experts in the Chicago Manual of Style. They have and are working for the top publishing houses (TOR, McMillian, Thomas Mercer, Penguin Random House, etc.) and elite indie presses.

We work with a small number of exclusive clients who want to collaborate with top-editors on an on-going basis.

Contact us today! If you would like more information, we invite you to email Kiffer or Sharon at KBrown@ChantiReviews.com or SAnderson@ChantiReviews.com